- Home

- Jeanette Arakawa

The Little Exile

The Little Exile Read online

The Little Exile

Jeanette S. Arakawa

Stone Bridge Press • Berkeley, California

Published by

Stone Bridge Press

P. O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

[email protected] • www.stonebridge.com

Text © 2017 Jeanette S. Arakawa.

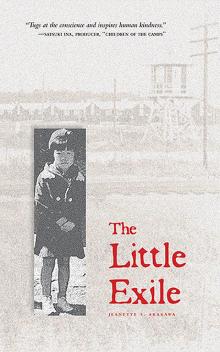

Front cover inset: Photograph of the author as a child, courtesy Jeanette S. Arakawa. Front cover background and frontispiece photograph: “Camp entrance, Jerome concentration camp, Arkansas, June 18, 1944,” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/sources/en-denshopd-i37-00798-1/.

Book design and layout by Linda Ronan.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data on file.

P-ISBN: 978-1-61172-036-5

E-ISBN: 978-1-61172-923-8

To Mama and Papa

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Afterword

An Epilogue Of Sorts

How This Book Came To Be

Acknowledgments

Note to the Reader

Although the characters in this story are fictional, the story itself is not. It is based on my childhood just prior to and just after World War II. It is a collection of recollections, over seventy years passed. From this vantage point, what I vividly recall are incidents devoid of much detail. The mundane of that period is missing from the store of my aging memory. As a result, the details I have provided to accompany the incidents are as I imagined they might have been. I have changed the names of the people in the story to protect their privacy, as well as their innocence in the event the details of my memory deviate significantly from theirs.

The songs and singers noted at the beginning of each chapter are intended to provide the ambiance of the period—music I recall hearing on the radio at the time.

Japanese was the language spoken in my home. That is to say, my parents spoke in Japanese with a sprinkling of English, and I responded in English sprinkled with Japanese. For expediency, and because of my inability to do dialects well, I have written most of the dialogue in my version of standard English.

Writing has caused me to retrace a journey long passed: occasionally joyful, occasionally painful. I believe that underlying everyone’s experience are threads that weave us all together into one large tapestry. It is my hope that you are able to find a common thread in my story as you read it.

JSA

CHAPTER 1

“Polly Wolly Doodle (All the Day)”

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

There was a Murphy bed in the apartment in back of a dry cleaning shop in the Polk district in San Francisco, California. It stood concealed behind a revolving panel door during the day and revealed itself every evening as it emerged from its hiding place and descended into the space where a dining table had previously stood.

On October 6, 1932, the dining table remained shoved into the corner, and the bed lay in the middle of the room, although it was mid-day. That’s because something very important was about to happen.

At exactly one o’clock, a stork magically appeared and plunked down its delivery in the middle of the bed. Me.

The stork got the time and place all wrong, but my mother said it wasn’t the stork’s fault. It was I who was so eager to join the family that I insisted on arriving a week early. According to Japanese custom, it was the year of the monkey. People born under this sign are supposed to be intelligent and clever, but mischievous. My parents named me “Shizuye” (Japanese for “quiet blessing”), in hopes that I would live up to my name, and not my sign. We were in the middle of “the Great Depression,” and my older brother, Brian, was just beginning to toddle. They didn’t need another challenge.

As I grew older, I loved standing at the front door of our dry cleaning shop, which was home to my parents, Brian, and me. By day the wood-framed glass door was a portal to the outside world. I watched people in passing cars and streetcars return my wave and saw tiny beads of water dance on the sidewalk when it rained. When I was lucky, I saw kids skating down the hill making sparks by dragging one skate as a brake. Or I saw a horse struggling to get its footing on the brick pavement and slippery streetcar tracks, as it pulled the junk-man’s wagon. Or I made faces at the organ grinder’s dancing monkey as he pressed his face on the glass.

Against the darkness of night, the door was magically transformed into a full-length mirror. Then I, Shizuye Mitsui, became the view. I, with my short, straight black hair with bangs cut in a line just above eyes shaped like quarter moons, floating on a face the color of plain Ovaltine. Walking, skipping, dancing, or just twisting my face into funny shapes.

One evening I came running from the back and headed straight for the closed door. I had just put on the new striped seersucker dress with matching white bolero Mama had sewn me. As I stood examining Mama’s handiwork and looking at my skinny arms jutting out of the broad sleeves, I caught a glimpse of Mrs. Terrace, our customer, out of the corner of my eye. I hadn’t noticed before that she was at the counter talking to my mother. I knew it was Mrs. Terrace, because she was wearing her brown coat with the dead red fox attached to the collar. Suddenly, the sickly smell of damp fur and stale perfume struck my nose. Too late to escape. I turned and looked up.

“You look just like Shirley Temple . . . ,” she said through puckered red lips as she bent down. She grabbed my cheeks in her gloved hands and lifted my face up. She drew it close to the glass-eyed fox that dangled from her neck. I didn’t like her, and I didn’t like her fox. I definitely didn’t look like Shirley Temple! Did I have blonde sausage curls that stuck out of the top of my head? Were my eyes round, and light brown, sitting deep in a dimpled and peach-colored face? My friend, Beverly Jensen, the Norwegian princess, looked like Shirley Temple. Maybe. But, not me. I wanted to pull away and run, but I had been taught to be polite. I said what I thought I should say.

“Thank you, Mrs. Fox.”

“Mrs. Terrace,” Mama corrected.

* * *

Beverly Jensen wasn’t really a Norwegian princess. We just pretended. I once wore a costume for a Buddhist church parade that included a delicate gold crown which sat perched on a little pillow on top of my head. I imagined I was a Japanese princess. I told Beverly about it, and that’s how the “princess” game got its start.

There was a box in the corner of the Helen Wills Playground clubhouse, where we often played. It brimmed with dresses, skirts, robes, scarves, and hats of every kind, shape, and color. My friends and I would find what we needed from the box to transport us to our parents’ native countries. I became a Japanese princess—Gina, an Italian princess—and Estella, a Mexican Princess. All our parents were immigrants, here to become Americans. It was fun to pretend we were in their countries.

In my case, many said that Papa resembled the emperor of Japan. They were both short, had mustaches and heavy curved eyebrows arched over dark round eyes. Although Madame Chiang Kai-shek was Chinese, some said that my mother, with high cheekbones, round hairline, and angular face, resembled her

. That didn’t exactly make me look like the princess of Japan. Actually, it didn’t make me anything. But I thought it was kind of interesting. Anyway, when my friends and I were together at the Helen Wills Playground clubhouse, the dress-up corner overflowed with “royalty.”

Beverly Jensen was my best friend. She lived in an apartment down Polk and around the corner on Broadway. We were the same age, but when we started school, she went to Sherman on Green Street across Van Ness Avenue, while I went to Spring Valley on Jackson on the other side of Larkin Street. We played together a lot because we could go to each other’s houses without crossing a street.

I had lunch at her house once.

“We’re having rice, Shizuye!” Beverly said. “You like rice, don’t you? You have to come over!”

She was right. I did like rice. Actually, I didn’t feel as though I had really eaten, unless the meal included rice. It was very nice of Beverly to invite me. I had never had lunch at a friend’s house before, so I could hardly wait until Saturday.

I was at her apartment shortly before twelve. Beverly met me at the door and led me to their breakfast nook in the kitchen. Mrs. Jensen was busy at the stove. She was heavyset and had very short “bobbed” hair, parted on the side and pushed into waves. She wore a pink apron splashed with different colored daisies, and ruffles that traveled along all the edges, including the straps. It belonged on a slender lady with long hair, I thought. But I didn’t say anything.

She looked up from the pot she was stirring and welcomed me.

“I’m so glad you’re having lunch with us,” she said. “Why don’t you take the seat next to the window.”

There were four matching white chairs around a matching white table. The chairs had tall backs that tapered to rounded pieces of flat wood decorated with flowers. They were supported by five rods that rose out of the backs of the seats. The rods were also handles for moving the chairs. I grabbed the rods in the chair closest to the window and dragged the chair back from the table and scooted into the seat. The table was set for two people. Beverly sat down across from me.

At my place, there was a large spoon placed on a red-and-white checkered napkin on one side of a bowl with a broad rim, and a knife, on the other. There was a small plate above the spoon and a glass above the knife. Rolls peeked out from under a napkin placed in a basket in the middle of the table.

“Thank you for inviting me,” I said as I sat down.

As soon as I was seated, Mrs. Jensen came to the table with her pot and started to spoon out little bits of white stuff into the unusually shaped plate. The rice I was accustomed to stuck together and was served in a bowl that I could pick up and put to my mouth. As I sat there wondering if I would be able to do that with this strangely shaped dish-bowl and move the rice across the brim without spilling it, she leaned in between my eyes and the rice. In her right hand, she held a spoon brimming with sugar and moved it like a wand over the rice and sprinkled the white dust all over it. Then came the milk. As soon as her right hand finished its job, her left emptied the contents of a small pitcher over the sugared rice. I watched as the little grains of rice struggled to stay afloat in the sea of milk. Soon the mound flattened and sank out of sight. She repeated the sugar and milk thing on Beverly’s rice.

As soon as Beverly was served she sat up in her chair and rubbed her hands together. “Hmmm,” she said. “Rice is my favorite thing to eat!” Then she stirred and spooned it to her mouth. She closed her eyes and smiled as she chewed and swallowed.

I watched her in amazement. Well, she seems to be enjoying it, it probably isn’t as bad as it looks, I thought.

Then she looked up and said, “Why aren’t you eating?”

I smiled and picked up the spoon. I stirred and scooped a little and put it in my mouth.

I loved rice, I loved sugar, and I loved milk. So, how could all the things I loved so much taste so bad when they were all put together?

Then to my surprise, Mrs. Jensen said, “You don’t have to eat it, if you don’t want to, Shizuye.” That’s amazing, I thought. She was able to read my mind! I put down my spoon and filled up on rolls.

* * *

What I liked best was skating with Beverly on the sidewalks around our block. It was our goal to be able to skate down Van Ness Avenue all the way from Pacific to Broadway. But we weren’t able to control our speed down the steep and slick hill. We had conquered Polk Street, though, which was as steep as Van Ness, but older and slower. Parts of the sidewalk, broken down over the years, had been replaced by a hodgepodge of rough squares of cement, which slowed us down. There were also lamp posts on the right edge of the sidewalk that we could grab if we were going too fast or trying to avoid pedestrians emptying out of the stores or apartments along the way. But, of all the streets, flat, smooth, broad Pacific Avenue was the most fun. We had only driveways to the auto repair shop and garage to contend with. We could do fancy stops and turns and pretend we were the ice-skating movie star Sonja Henie. Sonja Henie was from Norway, just like Beverly’s grandmother.

“When I was in Los Angeles visiting my cousin, I was able to jump off high curbs with my skates, because there was almost no traffic,” Beverly said.

That sounded exciting. I hoped that I would be able to go there someday and see for myself.

* * *

Beverly also played violin. When I went over to her apartment one morning, she opened the door, and to my surprise, she had a violin sticking straight out of her neck through a folded hanky. Tears were streaming down her face. It must be as painful as it looks, I thought. But it turned out it wasn’t the violin that was making her cry. It was her mother.

“Beverly!” she screamed from the kitchen. “You know you can’t go out until you finish practicing your violin! I told you not to answer the door!”

Beverly told me later that her mother wanted her to play violin, because she was a great fan of Yahoody.

“What’s a ‘Yahoody’?” I asked.

“You’ve never heard of Yehudi Menuhin?” she said dropping her jaw.

“He’s a famous violinist! The most famous in the whole world! And you haven’t heard of him?” She went on, “And he started playing when he was three.”

“Oh. So you’re going to be a famous violinist like Yahoody.”

“My mother would like that.”

“Well, I’m going to be a famous singer some day. And I would like that. I don’t know about my mother.”

“I’ve heard you sing, Marie,” said Beverly. “And you need to practice more if you want to be famous.”

When we weren’t playing at Beverly’s, we were at the playground. Actually, that’s where we first met. The playground was on Broadway, but across Polk Street. It was down the hill, across the street, and around the corner from the cleaners. Brian, who was two years older, took me most of the time. When he didn’t, Mama watched for traffic as I dashed across Polk Street to the furniture store with the enormous “ufolstreer” sign stretched across the top of the building. Going home, I looked for the nice lady with dark wavy hair and thin milky skin in the store to get me back across safely. Thin blue lines traced paths on the side of her forehead. Mama said those were blood vessels that could be seen through her thin skin. She was tall and skinny. Mrs. Jensen’s daisy-covered apron would have been perfect on her.

“Thank you, ufolstreer lady,” I would say. She would just smile.

One of the proudest moments of my life was when I figured out what that sign above the entrance to the store actually read.

Brian was disgusted with me for calling her the “ufolstreer” lady. He wouldn’t say the word properly for me, but he helped me figure it out.

“Try to break the word down into syllables,” he said. “You’re making the word more complicated than it is.”

“Up-hol-ster-er. Upholsterer!” I shouted.

“About time . . . ,” said Brian. I was six.

I could hardly wait to use it. The next day, after playground, I told Bria

n to go home without me, so I could get help crossing Polk.

“Upholsterer Lady! Upholsterer Lady!” I shouted into the store.

She ran from the back with outstretched arms and scooped me up.

“You’ve finally figured out how to pronounce ‘upholsterer’!” she said as she held me tight. “You’re all grown up now! Let me show you what it means.” She took my hand and led me to the back of the store.

“From now on, please call me Mrs. Pringle,” she continued. We walked through the neat, orderly showroom to the back of the store. There in the large work space were skeletons of chairs and sofas stripped bare of their stuffing and covering. It was as messy as the front area was neat. On one side of the room cluttered with bits of fabric, white puffs of cotton, and scraps of wood, a woman was hunched over a sewing machine stitching together oddly shaped pieces of material. A short distance away, a skinny man in dirty white coveralls and straggly brown hair on the edges of his balding head and upper lip tugged and pulled on a beautiful blue cover and stretched it over a padded chair. Then he pulled the nails that stuck out like stiff whiskers from under his mustache and hammered them into place to hold the cloth.

“Does he ever swallow a nail holding them in his mouth like that?” I whispered to Mrs. Pringle.

“No. But don’t you try that at home,” she said and then continued, “When a chair or sofa gets worn out, many people choose to have it reupholstered rather than throwing it out. That’s another way of saying we replace the stuffing and cover it with new fabric.“

As she spoke I thought about our sofa at home. It had a nasty stain on it from the time Brian cracked a raw egg on my head. He said he thought it was hard-boiled. Because of the lump on my head he created, Mama’s attention was then focused on me and my gummy hair, and she didn’t get around to the sofa until much later. By that time, the stains were set.

“We have a sofa at home that could use upholstering.” I told Mrs. Pringle.

“I can come over sometime and take a look,” she said as we walked out of the store.

The Little Exile

The Little Exile